A year ago, Jorge thought obtaining a Russian passport would be his ticket to freedom and wealth. Instead, it brought him a seemingly endless stint risking his life in Moscow’s brutal war against Ukraine.

The Cuban recruit is among thousands of foreign nationals who signed a one-year contract with the Russian army, lured by the promise of hefty paychecks and fast-tracked citizenship for themselves and their kin.

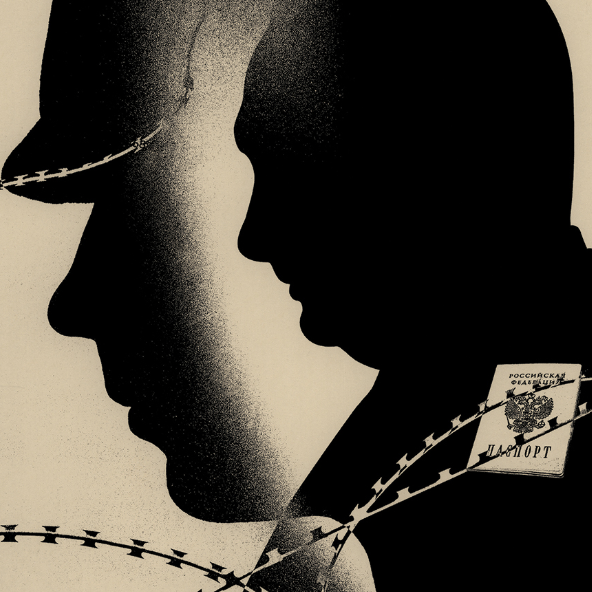

For Cubans, many of whom see life under Havana’s dictatorial regime and American sanctions as amounting to an open-air prison, the promise of a second passport has been a major draw. The document, however, comes with a noose attached.

“Now they’re telling us that, since we’re Russian citizens, we have to continue fighting until the end of the war,” said Jorge, speaking from Russia’s Kursk region where Moscow’s troops are trying to beat back a Ukrainian offensive. Like others interviewed for this article, he has been given a pseudonym for safety reasons.

Jorge’s story and those of three other Cuban recruits in Ukraine and Kursk, as well as the families of five others, offer new insight into how Moscow is trapping foreigners — as well as its own citizens — on the front line as it attempts to exhaust Ukraine and its Western backers while cushioning its own population from the impact of protracted war.

Foreign recruitment

With Russian casualties piling up since the launch of its full-scale invasion in February 2022, Moscow has reached across the globe for replenishments. Through shady intermediaries, fighters have been drafted from a host of countries including Nepal, Ghana, Syria, India and Sri Lanka.

Though the exact number of foreign recruits is a well-kept secret, the general consensus among military experts is that they form just a fraction of the Kremlin’s army fighting against Ukraine; plugging holes, rather than defining the momentum, on the battlefield.

Politically, however, their presence has been exploited by Moscow to push a Cold War-style narrative that Russia is leading a broad-based coalition of countries fighting back against American hegemony.

Cubans will recognize that trope from Soviet times, when they were deployed to Angola in their tens of thousands to help fight a proxy war against the U.S.

Hardly any of the Cuban recruits interviewed by POLITICO for an earlier story, however, offered up ideology as a reason behind their enlistment.

Rather, some said they had been hoodwinked into traveling to Russia after responding to posts on social media for what they thought would be low-skilled, civilian jobs, often in construction.

Others admitted they had willingly and consciously responded to Russia’s war call, citing financial difficulties and family responsibilities as driving their decision to board a flight to a place they had never visited before and knew almost nothing about.

In Cuba, they said, they had scraped to make a living as teachers, carpenters, waiters and in construction. A year of military service, they hoped, would buy them a new nationality — and with it, a new life.

Passport curse

Twelve months on, the Cuban recruits and their families say, their new passports turned out to be less a guarantee of more rights than the certification of a demotion: from poster boys of international solidarity to regular, mobilized Russian citizens — a status that few native-born Russians would envy.

In September 2022, Russian President Vladimir Putin’s announcement of a “partial mobilization campaign” plunged the country into a state of shock. For the first time since the full-scale invasion, Russia’s own population was confronted with the reality of the war and asked to pitch in with their lives.

While the campaign triggered a mass exodus of young men, hundreds of thousands nonetheless answered the call — some out of a sense of patriotic duty, many others out of what they felt was a lack of choice or for fear of retribution.

Those mobilized expected to be discharged before too long, after Russia’s supposedly imminent victory, or, at the very least, replaced with fresh boots on the ground.

Instead, they have been held at the front for two years and counting as Putin has stalled ordering a second mobilization drive in hopes of avoiding another societal meltdown. To replace casualties, he has relied on attracting more volunteers, offering locals high salaries as well as expedited citizenship for foreign recruits.

Meanwhile, mobilized Russians and their families have been given to understand that only the end of the war can bring the end of deployment. As the Cubans are finding out, newly minted Russians, even if they only signed up for a one-year stint in the army, are no exception.

“They’re using citizenship to tie us down,” David, another Cuban recruit whose contract officially ended in July, said in a video call. “That sounds like blackmail to me.”

David said he last saw his Cuban ID in October 2023, when it was confiscated by his military superiors. Shortly after, his Russian passport — issued only weeks earlier — was also taken from him, under the guise that it was safer to cross into Ukraine without it.

Others haven’t even caught so much as a glimpse of their Russian passports.

While some recruits were awarded citizenship within weeks of arriving in Russia for military training, there are those who are still waiting to receive the document more than one and a half years after enlisting.

“They don’t want to let us go,” said Manuel, a recruit who was among the first wave of Cubans to travel to Russia and has yet to receive a new passport. His Cuban documents were taken from him shortly after arrival, leaving him with only his military ID.

Ivan Chuviliayev, a member of the rights group Idite Lesom, which helps mobilized Russians flee the front, said Manuel’s situation was typical of the way Moscow tries to increase its leverage over foreign recruits.

“They don’t have any documents,” said Chuviliayev. “Those are in possession of the defense ministry. So they can’t just run away and appeal to their country’s embassy.”

Dara Massicot, a defense analyst at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, agreed.

“Foreign fighters should know that if they sign a contract with the Russian military or accept a passport from them, they are signing up to fight indefinitely in Ukraine until the Kremlin declares an end to the operation or they are killed or seriously injured,” she said.

Havana complicit

In the case of Cuba, it is unlikely that such a cry for help would make any difference.

After media reports that hundreds of Cubans had traveled to Russia to fight its war surfaced in September 2023, authorities in Havana denounced the men as “mercenaries” — an offense punishable with jail time in Cuba — and launched proceedings against the supposed recruiters.

At the time, the regime’s critics questioned how a dictatorship that keeps close tabs on its population’s every move could have failed to notice planeloads of men of fighting age heading to Moscow.

Events since then seem to further justify their skepticism. While India has lobbied hard to get its own citizens back, securing the release of 45 fighters this September and working towards bringing home 50 others, evidence suggests the recruitment of Cubans has continued, while Havana has publicly kowtowed to Putin.

In May, Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel was among the handful of dignitaries to attend the Kremlin’s highly symbolic Victory Day celebration. In filmed comments, he offered Putin “Cuba’s support” and wished him “success with your special military operation,” undoubtedly pleasing the Russian president by using his preferred euphemism for the war.

Cuba relies on Russia for crude oil and wheat. But where Moscow’s allies like Iran and North Korea have provided drones and artillery, impoverished Cuba has little else to offer than honeyed words and, according to Ukraine, manpower.

“In Cuba, there is a state-approved system, where they condone sending their own citizens to Ukraine to their death,” Petro Yatsenko, a spokesman for Ukraine’s agency for prisoners of war, a branch of Ukraine’s defense ministry, told journalists in March. (The agency did not respond to a request for comment.)

Yatsenko noted an uptick in the number of foreign soldiers captured in 2024, with Cubans top among them. “The percentage of mercenaries is growing, it’s growing significantly,” he told a press conference during which several foreign POWs, including a Cuban, were put on display.

That was months before North Korea sent thousands of troops to Russia to help bolster its presence in Kursk.

A U.S. congressional staffer who works on Cuba policy, granted anonymity to speak freely, said that it’s unlikely Havana wasn’t aware of the recruiting efforts before the first media reports.

“It was pretty transparent that they were turning a blind eye to it and were actively participating in it,” said the staffer. “Cuba was caught doing it, and nothing really happened. And so now other countries see that the consequences are sort of minimal so they can do it as well.”

Publicly, Moscow’s officials and propagandists retort that there are foreign fighters on Ukraine’s side, too.

But while Ukraine does indeed recruit foreign fighters, Massicot, the military analyst said, “they are treated very differently — those who volunteer for Ukraine sign contracts and can leave at the end of their contract.”

The Russian Defense Ministry did not respond to a request for comment. Neither did the Cuban Foreign Ministry or Cuban Embassy in Moscow.

Ticking time bomb

For the Cubans tethered to Russia’s war, the extension of their time on the battlefield beyond their stipulated contract is no formality; every extra minute on the front means a greater risk of physical or mental injury, and greater proximity to death.

“If only I could’ve dug trenches,” David said, his voice breaking. “This past year I did what I said I’d never do, but it was kill or be killed and I have four children to take care of.”

The idea that there was a clear deadline to his time in the Russian military had kept him afloat in his first year, he said. “I made a pact with God for one year, and He protected me. But not, two years or three,” he continued tearfully. “I don’t wish it upon anyone to wake up in the morning facing the choice between suicide or murder.”

Like every Cuban recruit interviewed by POLITICO, David had suffered shrapnel injuries from Ukrainian drone or missile strikes, but had been sent back to the front after medical treatment, sometimes before the stitches had healed. While being treated in hospital for a drone injury to his right hand, Pablo, who said he’s also been diagnosed with PTSD, was told by his commander that he’d just have to learn to shoot with his left.

Though many recruits said they had been stationed in rear positions, tasked with digging trenches and fortifications in Russia-occupied areas of eastern Ukraine, others have been deployed to the “first line” of assault, including to Kursk.

“It’s on fire over there,” said Jorge. A man with whom he made the initial journey to Russia over a year ago had died only several weeks earlier in a missile attack, he said. POLITICO confirmed the death through a relative in Cuba.

Spanish-language media working out of the U.S. have reported numerous Cuban casualties. But in Cuba itself, such news never makes the airwaves. Silencing it altogether, however, has proven impossible, with relatives of those deceased leaving a trail of online eulogies and tearful posts on social media.

The recruits said that news of a death is usually communicated informally, most often through WhatsApp by other Cuban recruits on site. They added that Cuban soldiers themselves will often pitch in money for a deceased person’s relatives to fly in. Those who wanted a burial in Cuba, not Russia, reportedly have to pay for the cost themselves.

In at least some cases, Cuban recruits simply seem to vanish into thin air. With neither Havana or Moscow showing much interest in their fate, and being off the radar of rights groups which help mobilized Russians, Cuban relatives thousands of kilometers away are often left to draw their own conclusions when their loved ones go AWOL.

In July, media reported that Denis Frank Pacheco Rubio, a 42-year-old recruit from the city of Santa Clara, had died in an assault on Siversk, north of Donetsk. His contract had been scheduled to end four months earlier, in February.

Months later, his sister said she had yet to receive any news on his remains. “We have gone everywhere, but no one will answer our questions,” she wrote in a message.

‘A way out of here’

Facing an open-ended dance with death, some recruits have attempted to flee the front and some have succeeded.

After hearing in the hospital that he was going to be sent back to the front line once again, despite his injuries and the fact he’d surpassed his contract by four months, David managed to hitch a ride and flee.

He now lives in hiding in a secret location while looking for a way to escape Russia without any documents — and without knowing where to go. “Cubans like me are just as afraid of Cuba as they are of Russia,” he said.

For many recruits, the stories of escape offer a rare source of optimism. “It gives us hope that there’s a way out of here,” said Jorge. But, he added, those who were caught risked being charged with desertion or being sent to front-line positions, to near-certain death, as punishment.

One recruit, Carlos Estrada González, was held in a pit without food for six days after one of his comrades successfully escaped, a relative told POLITICO. “They [the Russians] suspected that he’d known about it,” the person wrote in a message on Facebook.

After being released from his purgatory, he had told his family he wanted to flee and return home but that he didn’t know how without a passport.

Several days later, he stopped responding to messages. That was in mid-April.

“I feel in my heart that he’s still alive,” González’s son Javier wrote in a message from Cuba, alongside a screenshot of his father’s last known location on the outskirts of the city of Donetsk in Russian-occupied Ukraine.

Not wanting to run the risk of punishment, three of the four recruits whose one-year contracts had expired, said they preferred to stay put and place their faith in a higher power.

“All I can do is wait,” Manuel wrote, “and pray to God that one day I’ll be allowed to leave this place. As a free man.”

Eric Bazail-Eimil contributed reporting from Washington D.C.