Familiar trends characterized a year marked by elections and bloodshed.

BRUSSELS ― In 2024, you’d be forgiven for feeling a distinct sense of déjà vu.

Syria was back in the news, European leaders had to focus again on migration and, across the Atlantic, Donald Trump is preparing for his return to the White House, sending more shock waves through the political establishment in an unprecedented year of elections.

The wars that defined 2023 continue to rage, in some cases escalate, at great cost to human life.

And, as our charts show, even all that could be overshadowed by the threat posed by a world getting hotter, which looms over humanity’s future. Despite a plethora of warnings from scientists and international organizations, countries are still failing to contain global warming — and, if his rhetoric is to be believed, Trump’s second term could further weaken the international effort.

So this holiday season may not feel as jolly as it should. But as we hope for cheerier news in 2025, POLITICO’s data journalism team is here to illustrate how the old year played out.

War, war and another war

With over 44,500 Palestinians dead and a further 105,000 estimated to be wounded, according to the Hamas-controlled Ministry of Health, the humanitarian cost of the Israel-Hamas war continues to rise.

Geospatial analysts estimate that almost 60 percent of buildings in the Gaza Strip had likely been damaged by November 2024, meaning many of the 1.9 million internally displaced people there will have no home to return to.

The Israel-Hamas war increased hostilities across the region, with assassinations, bombings and missile barrages spilling the Iran-Israel proxy conflict into the open. After almost a year of exchanging missile strikes, conflict between Israel and Hezbollah peaked in October, with Israel’s ground invasion in southern Lebanon, although attacks reduced significantly following a cease-fire agreement.

In neighboring Syria, the dramatic overthrow of Bashar Assad’s regime, swiftly followed by Israeli airstrikes on the country’s weapon stocks and the arrival of ground forces via the demilitarized zone, increased uncertainty in the region.

At the other end of Europe, Russia’s war in Ukraine continues. Ukrainians chalked up some successes in 2024, becoming a dominant force in the Black Sea despite the country’s tiny navy, and mounting a counteroffensive into Russia’s Kursk region in August. But they are ending this year on the back foot, having lost many of their territorial gains and having seen many of their soldiers killed.

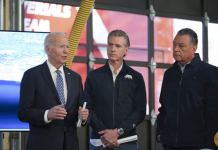

Blockbuster election year

With votes in more than 60 countries including France, the U.K., Bulgaria, India, Japan and the U.S., as well as for the European Parliament, 2024 was a huge election year. As right-wing forces broadly consolidated their position firmly in the political mainstream, the polls themselves saw social media platforms like TikTok have ever greater influence and even shape campaigns.

Europe’s lurch to the right was on display in many of this year’s votes. In some countries, far-right parties rose to power; in others, they gained a position to exert significant pressure on governments.

Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni’s right-wing European Conservatives and Reformists became EU power brokers after the June European Parliament election. French President Emmanuel Macron’s shock decision to call a snap election in the aftermath of the EU vote plunged the country into political chaos.

What was interesting is that the far right’s success in many of the votes called for an update to the stereotypical image of their voters being angry old men.

Instead, elections, exit polls and surveys in different parts of the bloc suggested young voters were increasingly throwing their support behind far-right parties.

A German youth survey showed the growing popularity of the Alternative for Germany party among the country’s youngest voters.

The forecast that artificial intelligence would take over our democracy did not quite come to pass — but recent events offered us a chilling preview.

In December, Romania’s top court annulled a presidential election after ultranationalist underdog Cǎlin Georgescu won the first round, citing evidence of widespread interference and a TikTok influence operation — allegedly orchestrated from Russia.

And while TikTok did not give Europe’s far-right forces an outright victory in June’s European Parliament election, it did provide them with a huge platform to reach new voters.

Panic about migration like it’s 2015

Wars and political instability in the EU’s neighborhood, coupled with a marked rightward shift in the political landscape, put migration firmly back on European leaders’ agenda. A surge in support for hard-right, anti-immigration parties in several European countries led governments to adopt increasingly restrictive policies.

Gone are the days of Europe’s open-door policy for Syrian refugees, epitomized by then-German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s slogan “We can do it!” Securing Europe’s borders has become the No. 1 priority, and in some places the political debate has even started to include removing migrants from the EU’s territory entirely.

Brussels has been no exception to this reality. The European Commission, reconstituted on Dec. 1 under President Ursula von der Leyen (who was confirmed by a right-leaning majority in the European Parliament), has already promised to get tough on migration. Policies once considered fringe and extreme, such as setting up “return hubs” and “hot spots” in third countries to hold asylum-seekers waiting for their claims to be processed, as well as forced deportations, are now firmly in the political mainstream.

Schengen — the world’s largest free-travel area and a crown jewel of European integration — is also falling victim to anti-immigration sentiment. Several countries including Germany have reintroduced temporary border controls within the zone, citing security risks, terrorism and migration as reasons for the renewed checks. These restrictions are supposed to be temporary, but some have been extended so many times that they have become nearly permanent.

The latest U.N. assessment confirmed that global climate action is woefully insufficient. Current plans and policies will lead to 2.6 to 3.1 degrees Celsius of global warming this century, with no prospect of limiting the temperature increase to the 1.5C target. The Paris Agreement’s upper limit of 2C is also at grave risk.

The severity and frequency of dangerous heat waves, destructive storms and other disasters rises with every fraction of warming. Scientists say that with warming of 3C the world could pass several points of no return that would dramatically alter the planet’s climate and increase sea levels, including through the collapse of polar ice caps.

This year’s COP29 climate conference in Baku, Azerbaijan, was once again marked by controversies and contradictions. While negotiators reached a deal that would see wealthier countries provide a minimum of $300 billion per year by 2035 to aid poorer nations in their battle against climate change, several analyses found that this amount falls far short of the trillions of dollars needed to help vulnerable countries that will have to withstand droughts and floods, rising seas and worsening storms.